The English villages that are hotbeds of murder, intrigue and endless summer days — at least in the minds of novelists

Comforting yet complex, intriguing and alluring, the village setting is territory to which writers — and readers — will return again and again. Flora Watkins looks at how the customs, characters and communities of the English village have long sparked literary inspiration, from Jane Austen to Midsomer Murders.

As an attentive aunt, Jane Austen was keen to encourage her niece, Anna, with the novel she was writing. ‘Three or four families in a country village is the very thing to work on,’ she wrote to her in 1814, adding, ‘such a spot… is the delight of my life’. We do not know what became of Anna Austen’s novel, but the manuscript on which her aunt was working at the time — Emma — in just such a setting, would become her masterpiece.

Emma takes place in the fictitious Highbury in Surrey, a ‘large and populous village almost amounting to a town’. We are told it is some seven miles from Box Hill, where the pivotal picnic scene takes place at which Emma insults Miss Bates, prompting the examination of character that eventually brings the heroine to realise she loves Mr Knightley.

Whether Highbury in Emma or Meryton in Pride and Prejudice, Austen rarely strayed, in her imagination, from the village life of her childhood, spent at Steventon Rectory in Hampshire where her father was vicar. As Claire Tomalin observes in her biography Jane Austen: A Life, the rupture from Steventon, when Austen’s parents retired to Bath, depressed her sufficiently to ‘disable her as a writer’ for several years. It was only when she moved back to Hampshire after her father’s death, settling at Chawton, that her creative powers were restored. Here, she revised Sense and Sensibility, enjoyed success with Pride and Prejudice and completed work on Mansfield Park and Emma.

The social environment of a village provided Austen not only with inspiration, but the perfect surroundings in which to write. Village life is a gift to novelists writing in many different genres, whether literary fiction, such as the Booker-nominated Harvest by Jim Crace, crime (Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd), sci-fi (The Midwich Cuckoos) or ‘Aga saga’ (Joanna Trollope’s A Village Affair).

Here at once is a microcosm of society: the manor house with its squire — although, today, the manor is more likely to be occupied by a hedge-fund manager — the rectory, cottages and even social housing on the outskirts. This was the setting that the best-selling ‘Harry Potter’ author J. K. Rowling chose for her first novel for adults, The Casual Vacancy. When a member of the parish council in Pagford dies suddenly, deep divisions and rivalries are exposed.

Tensions within a village are also central to Claire Fuller’s critically acclaimed Unsettled Ground, which was short-listed for the Women’s Prize for Fiction. Set in the fictional village of Inkbourne in Wiltshire, the two main characters, Jeanie and Julius, are 51- year-old twins who still live with their mother in a dilapidated cottage.

Villages, the writer believes, ‘are really fertile ground for all sorts of reasons. Everybody knows everyone else and has an opinion about them, whether that’s right or wrong. If you have any oddballs or eccentrics in a small community, they can’t hide’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

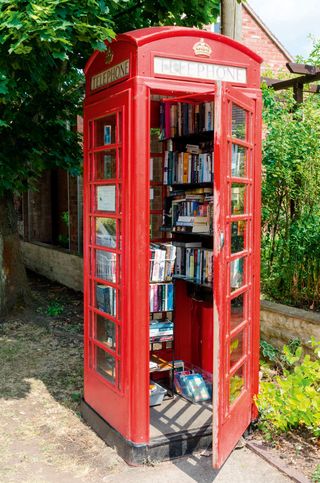

In the novel, Inkbourne — a hybrid of Inkpen and Shalbourne, on the North Wessex Downs — is undergoing gentrification with its new delicatessen, in which the impoverished Jeanie sells her eggs and vegetables. Disparities in wealth are especially visible in a village, Miss Fuller observes, adding that, increasingly, there is a new kind of wealth in technology and who has access to it. ‘In Unsettled Ground, one telephone box has become a library, the other has a defibrillator in it. If you don’t have a phone, what do you do?’

Eccentrics abound in one of Miss Fuller’s favourite novels about village life, Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns. Ducks come swimming through the drawing-room window when the river floods, an old woman with a giant ear trumpet bullies her granddaughters and villagers go mad due to a strange epidemic.

Characters can sometimes, however, veer into cliché in a village setting. In The Murder at the Vicarage, the first ‘Miss Marple’ mystery, Christie populates St Mary Mead with gossiping ‘old cats’, a small-time poacher bearing a grudge, troublesome domestic staff and a tennis-playing young girl reminiscent of John Betjeman’s Joan Hunter Dunn.

‘People who live in a village are as complex as people who live anywhere else, but there is a certain shorthand that we all recognise, starting from Miss Marple,’ says Miss Fuller. And, as Jane Marple is fond of observing: ‘Human nature is much the same everywhere, and of course, one has opportunities of observing it at closer quarters in a village.’

Human nature is the livelihood of Emma Howick, the anthropologist in Barbara Pym’s A Few Green Leaves. Through her eyes, Pym examines the quiet changes that time has wrought on the community, such as the declining congregations and the manor house that was once at the centre of village gatherings, but is now off-limits.

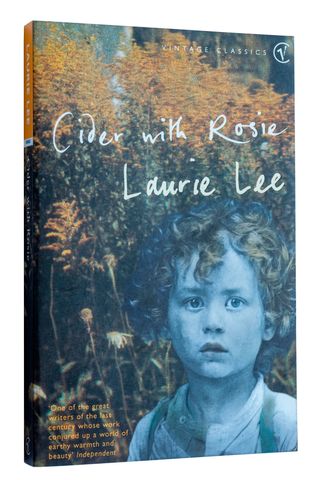

That lost way of life has never been evoked more vividly than in Cider With Rosie, Laurie Lee’s gorgeous memoir of growing up in the then remote Cotswold village of Slad. ‘I belonged to that generation which saw, by chance, the end of a thousand years’ life,’ he recalled. ‘A world of hard work; of villages like ships in the empty landscapes; of white narrow roads, rutted by hooves and cart-wheels, innocent of oil and petrol.’

In a similar way, Flora Thompson’s semi-autobiographical ‘Lark Rise to Candleford’ trilogy portrays a vanished world of agricultural customs, seasonal celebrations and churchgoing. Lark Rise is based on Juniper Hill, the hamlet in north Oxfordshire where Thompson was born in 1876.

However, the most direct depiction of changing rural life is surely Akenfield by Ronald Blythe. Although the name is fictitious, the testimonies that were gathered by Blythe from Suffolk villagers in the 1960s are often disquietingly frank. ‘People were content, however hard up they were,’ recalls the blacksmith, Gregory Gladwell, of his 1930s childhood. ‘The boys had their arse out of their trousers, no socks and the toes out of their boots. My brothers and I were life [sic] this, yet so happy.’

Lee admitted that some of the facts may have been distorted by time — rural poverty does tend to become picturesque when recalled down the years. Readers are aware that, unlike Emma Woodhouse, villagers are unlikely to have ‘very little to distress or vex’ them. However, the fantasy of the rural idyll abounds, which is, perhaps, part of the attraction of the village setting.

J. L. Carr’s exquisite novella A Month in the Country, set in Oxgodby in the North Riding of Yorkshire in the summer of 1920, is tinged with sadness, in the shape of unrequited love, injustices and failed relationships. Yet the shell-shocked veteran Tom Birkin finds a kind of redemption as he uncovers the medieval mural in the church.

‘I had a feeling of immense content,’ the narrator recalls, as an old man. ‘And, if I thought at all, it was that I’d like this to go on and on… summer’s ripeness lasting forever.’ Comforting yet complex, intriguing and alluring, the village setting is territory to which writers — and readers — will return again and again.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Jason Goodwin: The dark, chilly undercurrents in the seemingly-idyllic life of the English village

Jason Goodwin was feeling decidedly nostalgic for village life — until he had a run-in with one of its discontents.

How the architecture of the Cotswolds came to define the archetypal English country village

The architecture of the Cotswolds is almost intrinsically linked to popular conceptions of the English country village. Clive Aslet considers

-

The V&A and Burberry announce landmark Fashion Gallery makeover

The V&A and Burberry announce landmark Fashion Gallery makeoverThe V&A is renovating one of its largest and most-visited spaces — with support from British fashion house Burberry.

By Amie Elizabeth White Published

-

Bestwall Park: The six-bedroom house for sale that lives up to its name

Bestwall Park: The six-bedroom house for sale that lives up to its nameWith 17 acres, this Arts-and-Crafts gem is haven for both humans and wildlife.

By Arabella Youens Published

-

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen2025 marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen's birth. Here are exhibitions, events and more — happening across the UK — that mark the occasion.

By Annunciata Elwes Published

-

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winter

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winterFrom cookbooks to cricket, biographies to Sunday Times bestsellers, Country Life contributors name some of their favourite books from last year.

By Country Life Published

-

J.R.R. Tolkien: The life and times of the lord of the books

J.R.R. Tolkien: The life and times of the lord of the booksFrom a sentence born of an exhausting teaching job, J. R. R. Tolkien crafted a series of fantastical novels that, 50 years on from his death, still loom as large in our imagination as Sauron’s all-seeing eye, says Matthew Dennison.

By Matthew Dennison Published

-

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stile

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stileThomas Hardy’s depictions of a fictional Wessex and his own dear Dorset are more accurate than they may at first appear, says Susan Owens.

By Country Life Published

-

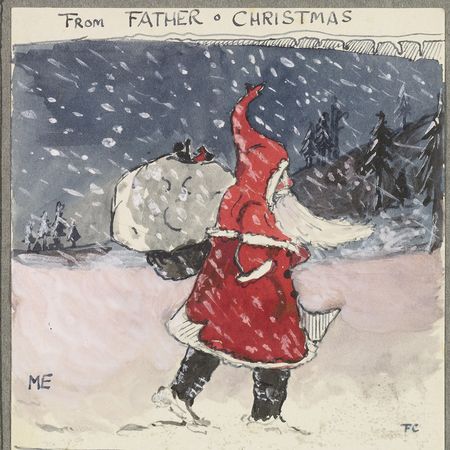

With love from Father Christmas: J.R.R. Tolkien's enchanting Christmas letters to his children

With love from Father Christmas: J.R.R. Tolkien's enchanting Christmas letters to his childrenFor nearly a quarter of a century, J. R. R. Tolkien sent his children elaborate letters and pictures from the North Pole. Ben Lerwill explores the penmanship, kindness and magic that went into Letters From Father Christmas.

By Country Life Published

-

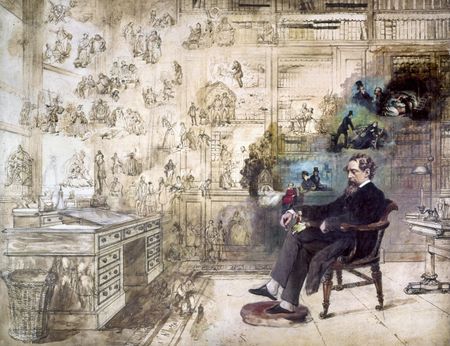

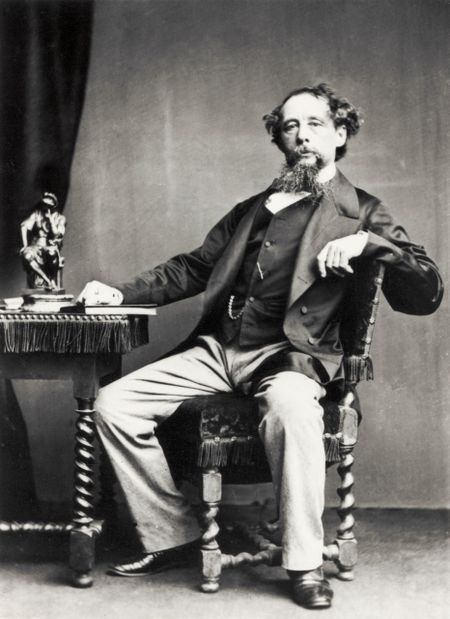

The best characters created Charles Dickens, still utterly unforgettable even 150 years after his death

The best characters created Charles Dickens, still utterly unforgettable even 150 years after his deathCharles Dickens died 150 years ago, on 9 June 1870. Since then, Mr Micawber has become a byword for optimism, Scrooge for meanness and Uriah Heep for obsequiousness, and we still quote Mr Bumble’s ‘the law is an ass’. Rupert Godsal explains why these characters are so exuberantly unforgettable.

By Country Life Published

-

Charles Dickens timeline: The best of times, the worst of times

Charles Dickens timeline: The best of times, the worst of timesRupert Godsal paints the major events in the life and times of Charles Dickens, who died 150 years ago on 9 June, 1870.

By Country Life Published

-

In Focus: The greatest books ever written about theatre, as chosen by Michael Billington

In Focus: The greatest books ever written about theatre, as chosen by Michael BillingtonMichael Billington has been the theatre critic for Country Life (and several other publications) for decades. With theatres closed, he's turned his hand to picking out his 10 favourite books about theatrical life.

By Michael Billington Published